Untangling Housing Affordability & Groundwater Regulation

Key Points

•To ensure long-term water supplies for current residents, the state has imposed limitations on some new housing subdivisions and other types of development.

•While the new limitations may increase the costs of new homes in some parts of the Greater Phoenix area, cities have a variety of strategies available to encourage lower cost development to mitigate those impacts.

Background

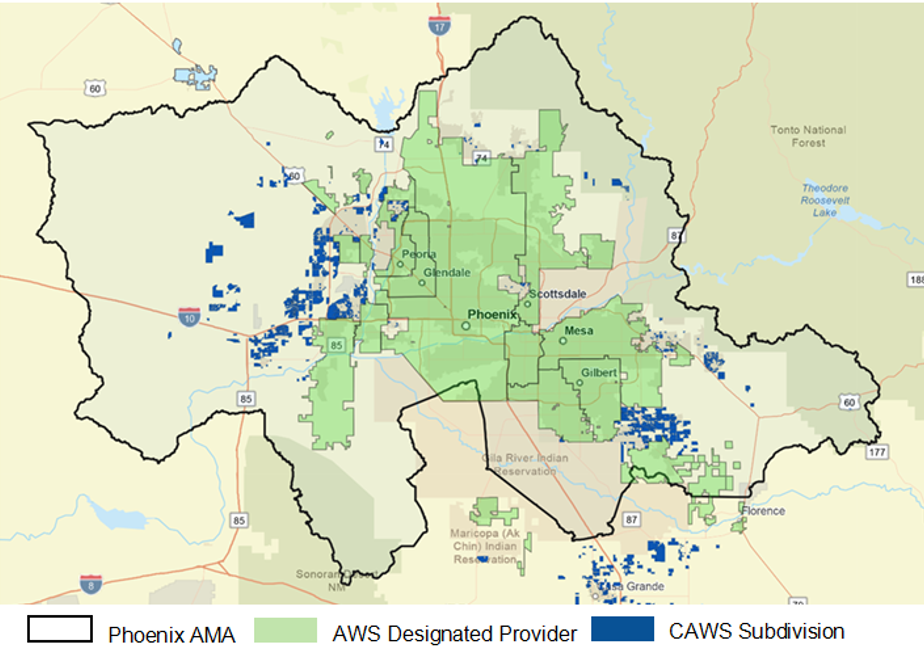

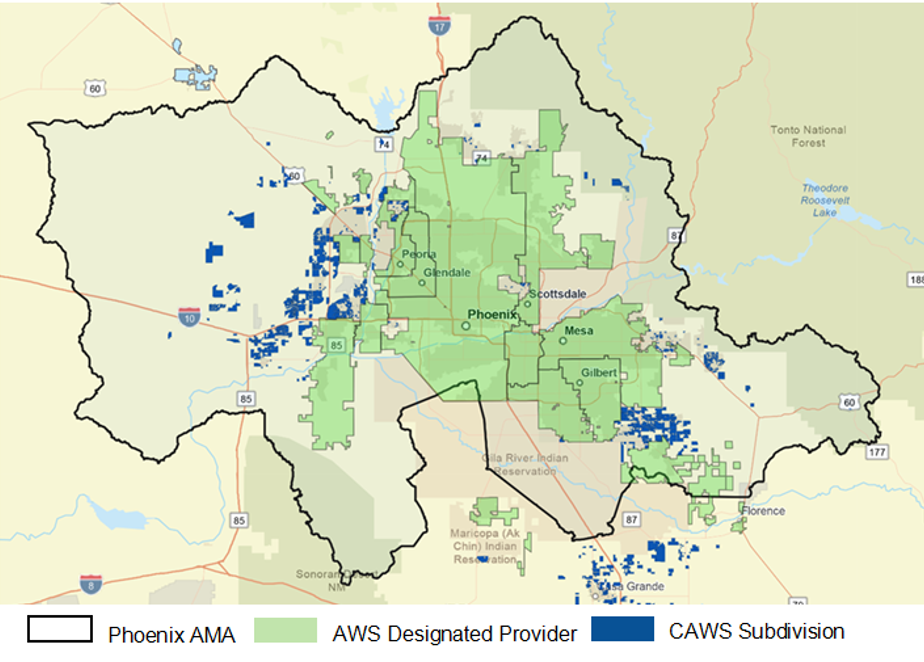

In June 2023, the State of Arizona published a new groundwater model for the Phoenix Active Management Area (AMA) triggering a moratorium on the issuance of permits for proposed subdivisions that would rely on local groundwater – that is, water in aquifers beneath the land to proposed for development. The Phoenix AMA, which covers the entire Greater Phoenix metropolitan area, is one of six areas in Arizona where groundwater use is actively managed through a series of rigorous requirements to ensure that groundwater remains available for future generations. In some of Greater Phoenix’s high growth suburbs, a permit called a “Certificate of Assured Water Supply” (CAWS) is required before a subdivision can be developed.

This means that in some parts of Greater Phoenix, new housing subdivisions will not be permitted unless the developers secure water supplies other than local groundwater. Securing alternative supplies will likely require costly and complex investments in both water and infrastructure, raising concerns that new home development will be slowed and the cost of new homes will increase, exacerbating local housing affordability problems.

This report examines how the new limitation on CAWS will impact housing affordability.

What parts of Greater Phoenix will be impacted by the new limitation on CAWS?

To protect home buyers, Arizona imposes rigorous water supply requirements for new subdivisions in the state’s most populated areas.[1] Before lots in a new subdivision can be sold, the developer must either:

- Obtain a commitment of water service from a water provider that has been designated by the state as having an Assured Water Supply (AWS) – known as a “designated water provider.” To be designated, a water provider must demonstrate at least every fifteen years that it has sufficient water to serve current, committed, and future demand for 100 years; or

- Obtain a CAWS by demonstrating that the subdivision has a 100-year supply of water that is physically, legally and financially available.

Most Phoenix area cities are designated water providers, serving well over 90% of the metro area population. The moratorium will not have an impact on new home development in those cities. However, some of Greater Phoenix’s fast growing areas – for example, the west valley city of Buckeye and the southeast valley town of Queen Creek – are not served by a designated water provider. Developers in these areas have historically favored local groundwater as the supply of water for a CAWS because it has been readily available and is typically less expensive to use than other options.

The Phoenix AMA groundwater model projects existing and permitted demand for the next 100 years. The model shows that there is insufficient legally available groundwater to meet all of the projected demand. As a result of this finding, the state will no longer issue CAWS based on local groundwater for new subdivisions in the AMA.

What is the housing affordability problem?

|

||||||||||||||||||

The US Department of Housing and Urban Development defines “affordable housing” as housing for which the occupant is paying no more than 30% of gross income.[2] “Attainable housing” is defined as housing that costs no more than 30% of the gross incomes of households earning 80% to 120% of the area median income.[3]

With the median price of homes in Phoenix climbing 39% between 2018-2022, both attainable and affordable housing have become less available.[4] Currently, 44% of Phoenix area renters are cost burdened, meaning they are spending more than 30% of their income on housing.[5]

Increases in housing costs “disproportionately impact lower income individuals,”[6] because lower income households typically spend a larger proportion of total income on housing than do higher income households.[7]

|

Will the CAWS moratorium make the housing affordability problem worse?

As noted above, most Phoenix area cities are designated water providers and development in those cities will not be impacted by the new moratorium. In addition, building may proceed in planned developments for which a CAWS has already been issued – potentially enough for over 80,000 new homes.[8]

|

Assured Water Supply Designated Water Providers City of Avondale City of Goodyear City of Surprise City of Chandler City of Mesa City of Tempe City of El Mirage City of Peoria EPCOR – Fountain Hills Town of Gilbert City of Phoenix EPCOR – San Tan City of Glendale City of Scottsdale Apache Junction Water Co. |

The CAWS moratorium may slow the pace of new home development in suburban areas not served by a designated water provider, potentially depressing total inventory and adding to other factors that increase housing costs in the metro area.

However, housing costs are influenced by a number of factors: federal interest rates, inflation, supply chain interruptions, migration patterns, remote work, labor markets, local, state, and federal government policies and regulations – to name a few.[9] A 2023 peer review of three recent analyses of Arizona housing affordability prepared for the Arizona League of Cities and Towns estimates that “macroeconomic influences [such as interest rates set by the US Federal Reserve Bank] represent between 85% and 90% of the current housing availability and affordability issues.”[10]

|

Available measures for incentivizing the development of lower cost housing:

Measures that are currently prohibited by state law:

* For further details, see Ashlee Tziganuk et al., Exclusionary Zoning: A Legal Barrier to Affordable Housing (May, 2022) and Katie Gentry et al., State Level Legal Barriers to Adopting Affordable Housing Policies in Arizona (Nov. 2022) as well as other Morrison Institute research on housing in Arizona. |

Policies within the control of local and state governments can also contribute to the region’s shortage of affordable housing.[11] In much of the Phoenix area, zoning and development codes promote lower density development, effectively discouraging the creation of lower cost housing.[12] For example, many municipalities zone at least 50% of their land for single-family use.[13] Restricting housing duplexes, triplexes and apartments limits potential supply and increases the per-unit cost of infrastructure such as roads and water, sewer and power lines.[14]

In contrast, creating higher density housing options that rely on the efficient use of existing infrastructure can lower costs per unit while also increasing the supply of housing at lower price points than single-family homes in newly built suburban subdivisions.[15] Moreover, denser development can reap community benefits, potentially generating greater tax revenue per acre than conventional suburban development and reducing fiscal burdens through more efficient use of public infrastructure.[16]

In the absence of economic studies, it is difficult to say whether or how the CAWS moratorium might impact housing affordability. In any case, local communities and the state have options to mitigate such impacts. As is the case with almost any public policy goal, housing affordability involves tradeoffs: The state’s Assured Water Supply Designation program ensures that designated water providers make up-front investments in long-term water supplies for the communities they serve.

This report was prepared by the Kyl Center for Water Policy in collaboration with our colleagues at Morrison Institute for Public Policy.

[1] Under Arizona law, a subdivision is the division of land into six or more lots for sale or lease for more than one year for residential, industrial or commercial use. See Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 32-2101(58).

[2] US Dep’t of Hous.& Urb. Dev., Barriers to Affordable Housing, https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/comm_planning/affordable_housing_barriers.

[3] Adam Ducker et al., Attainable Housing: Challenges, Perceptions, and Solutions. (2019), https://www.rclco.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Attainable-Housing3-Challenges-Perceptions-and-Solutions-ULI-Terwilliger.pdf.

[4] Rounds Consulting Group, Peer Review: Analysis of Housing Affordability in Arizona 14 (March 2023), https://www.azleague.org/DocumentCenter/View/23843/032223-Housing-Peer-Review. See also Arizona Housing Supply Study Committee, Final Report (December 2022) https://homefront.azhousingforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Housing-Supply-Study-Committee-Final-Report-2022.pdf, (finding that Arizona has a severe housing shortage).

[5] Liza C. Kurtz et al, “You Feel Like a Failure”: Experiences of Housing Insecurity in Maricopa County, (May 2022) https://morrisoninstitute.asu.edu/sites/default/files/experiences_of_housing_insecurity_in_maricopa_county.pdf

[6] Rounds Consulting Group, supra note 6, at 7.

[7] Id.

[8] Ariz. Dep’t of Water Res. Phoenix AMA Groundwater Model (June 2, 2023), https://new.azwater.gov/sites/default/files/media/2023_06_PhxAMA_Model_PublicMeeting_0.pdf.

[9] Rounds Consulting Group, supra Note 6, at 5.

[10] Id. at 4.

[11] Id.

[12] Ashlee Tziganuk et al., Exclusionary Zoning: A Legal Barrier to Affordable Housing 2 (May 2022), https://morrisoninstitute.asu.edu/sites/default/files/exclusionary_zoning_legal_barrier_to_affordable_housing.pdf

[13] Id.

[14] Tziganuk, supra Note 14, at 6-12.

[15] Nat’l Multifamily Hous. Counc., Multifamily Benefits: The Housing Affordability Toolkit, https://housingtoolkit.nmhc.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/D_NMHC_PDF-Sections_Multifamily-Benefits_PG-36-TO-44.pdf

[16] Id.